Statutes criminalizing the wearing of masks often have a “Halloween exception.” But in some states – – – Louisiana, for example – – – the exception has an exception for a certain type of person.

Statutes criminalizing the wearing of masks often have a “Halloween exception.” But in some states – – – Louisiana, for example – – – the exception has an exception for a certain type of person.

Here’s the statute, §14.313:

A. No person shall use or wear in any public place of any character whatsoever, or in any open place in view thereof, a hood or mask, or anything in the nature of either, or any facial disguise of any kind or description, calculated to conceal or hide the identity of the person or to prevent his being readily recognized.

B. Whoever violates this Section shall be imprisoned for not less than six months nor more than three years.

C. Except as provided in Subsection E of this Section, this Section shall not apply:

(1) To activities of children on Halloween, to persons participating in any public parade or exhibition of an educational, religious, or historical character given by any school, church, or public governing authority, or to persons in any private residence, club, or lodge room.

(2) To persons participating in masquerade balls or entertainments, to persons participating in carnival parades or exhibitions during the period of Mardi Gras festivities, to persons participating in the parades or exhibitions of minstrel troupes, circuses, or other dramatic or amusement shows, or to promiscuous masking on Mardi Gras which are duly authorized by the governing authorities of the municipality in which they are held or by the sheriff of the parish if held outside of an incorporated municipality.

(3) To persons wearing head covering or veils pursuant to religious beliefs or customs.

D. All persons having charge or control of any of the festivities set forth in Paragraph B(2) of this Section, shall, in order to bring the persons participating therein within the exceptions contained in Paragraph B(2), make written application for and shall obtain in advance of the festivities from the mayor of the city, town, or village in which the festivities are to be held, or when the festivities are to be held outside of an incorporated city, town, or village, from the sheriff of the parish, a written permit to conduct the festivities. A general public proclamation by the mayor or sheriff authorizing the festivities shall be equivalent to an application and permit.

E. Every person convicted of or who pleads guilty to a sex offense specified in R.S. 24:932, is prohibited from using or wearing a hood, mask or disguise of any kind with the intent to hide, conceal or disguise his identity on or concerning Halloween, Mardi Gras, Easter, Christmas, or any other recognized holiday for which hoods, masks, or disguises are generally used.

Masks generally prohibited, except on Halloween (or Mardi Gras or other holidays) except for those who have to register as sex offenders.

More about masking as well as persons who must register as sex offenders because of public nudity or indecent exposure is in Dressing Constitutionally.

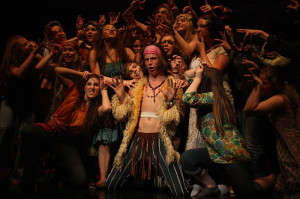

[image via]