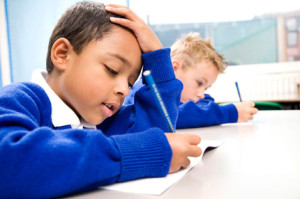

As reported, Principal Lorenzo Chambers of Brooklyn’s P.S. 279 sent a letter to parents in which he questioned their alleged religious motives for opting their children out of the school’s dress code.

In New York City, a public school can voluntarily adopt a mandatory uniforms for their pupils. At Brooklyn’s P.S. 279, the required uniform consists of polos and blue khaki pants, but students may be exempt from the mandatory dress code for several recognized reasons, including religious. New York City law provides that “students have a right to … determine their own dress within the parameters of the Department of Education policy on school uniforms and consistent with religious expression.” To avoid disciplinary action, parents have 30 days to apply for the exemption, and students can face suspension and other punitive measures for violating the uniform requirement.

In New York City, a public school can voluntarily adopt a mandatory uniforms for their pupils. At Brooklyn’s P.S. 279, the required uniform consists of polos and blue khaki pants, but students may be exempt from the mandatory dress code for several recognized reasons, including religious. New York City law provides that “students have a right to … determine their own dress within the parameters of the Department of Education policy on school uniforms and consistent with religious expression.” To avoid disciplinary action, parents have 30 days to apply for the exemption, and students can face suspension and other punitive measures for violating the uniform requirement.

According to the letter sent to parents last month, Principal Chambers became alarmed by parents claiming religious exemptions for their children after he deduced parents were falsely invoking religious expression claims “when clearly there are no such reasons.” He concluded this “because some of [the] children wore their uniforms last year and not this year.”

He added, “school is about learning, not about what we look like and asserting one’s individuality through what he/she wears,” and that “children should assert their individuality by who they are as a person — how hard they work or how kind they are to their peers or how respectful they are to adults.”

However, Chambers may be overlooking the real reason behind the alleged false exemptions — rather than parental concern over a child’s self-expression, parents may seek exemption from the mandatory uniform because, simply, uniforms are expensive.

Indeed, one P.S. 279 mother told reporters that she needed a month to save the money just to buy the uniform. “If you go to school without the uniform, they make you change and put one on … It’s not good sometimes if you don’t have enough money. It’s $15 for pants and $7 for a shirt. It adds up.” The uniform can be purchased online at Walmart.com.

Indeed, one P.S. 279 mother told reporters that she needed a month to save the money just to buy the uniform. “If you go to school without the uniform, they make you change and put one on … It’s not good sometimes if you don’t have enough money. It’s $15 for pants and $7 for a shirt. It adds up.” The uniform can be purchased online at Walmart.com.

While for some “it’s just a uniform,” for others who struggle to make ends meet, it can be a very serious expense with drastic consequences. And though the Constitution’s right to freedom of religion may afford a student exemption from the mandatory dress codes, unfortunately for many New York City families, economic hardship is not also protected in this way.

As far as the administration goes, the school might be better served if there were first inquiry into the reasons for claimed religious exemptions, rather than accusations of lying and telling parents they do a “‘disservice” to the community by opting out of purchasing uniforms. Indeed, given the outspoken critics of Principal Chamber’s letter, attempting to ameliorate the need for exemptions, rather than chastising parents, might just be a better strategy all around.

[image via 1 & 2]